Grievous Bodley harm?

The strange affair of Exeter's medieval manuscripts

with Ian Maxted on Thursday, 8 June 2023

at 7pm at Leonardo Hotel Exeter [Jurys Inn Exeter Hotel]

Our speaker, Ian Maxted , is editor of the Exeter Working Papers on Book History website, and the Devon Bibliography website which seeks to continue the work he did for the Westcountry Studies Library where he was local studies librarian from 1977 to 2005. His talk discussed the role of Sir Thomas Bodley in the history of the Exeter Cathedral Library and showed images of thirty of the manuscripts involved. The talk also covered the rebuilding of the Library in the North Cloisters in 1412 and ended with the long view on the rise and fall, and resurrection of, Exeter’s libraries over the centuries (This will be covered in Part Two of the write up). Ian kindly provided the typescript of his talk, portions of which will be copied for this account,

A previous version of this talk was given in 2018, together with an exhibition, on the occasion of the unveiling by Exeter Civic Society of a blue plaque to Sir Thomas Bodley. It has been updated following Exeter's designation in 2019 as UNESCO city of literature and the exhibition “Gatekeepers to Heaven” which has brought back to Exeter for the first time in more than four centuries six of the manuscripts, now in Oxford, but until 1602 in Exeter Cathedral Library. The often lengthy captions to the images are taken from the 2018 exhibition and the images are reproduced courtesy of the Bodleian Library.

Sir Thomas Bodley

Sir Thomas Bodley, the cause of the removal of almost 100 medieval manuscripts from Exeter to Oxford in 1602 came from good Devon stock, rooted in Dunscombe in the parish of Crediton, just over the border from Newton St. Cyres.

He was born in 1545 at 229 High Street, Exeter, the son of merchant and fervent Protestant John Bodley. In 1553 he fled with his father and the young miniature painter Nicholas Hilliard to Geneva, returning in 1558 and settling in London, where in 1562 John Bodley received a patent to publish the Geneva Bible. In 1563 Thomas took the degree of BA at Oxford, and in 1566 at Merton College the degree of MA, being elected University proctor in 1569. In the late 1570s he travelled in Italy, France and Germany and in 1580 was appointed gentleman usher to Queen Elizabeth. He became MP for Plymouth in 1584 and for St Germans in 1586. His first diplomatic mission, to the Danish court, was in 1585.

Key to Bodley’s secret cipher

He probably combined spying with diplomatic activities as his secret cipher indicates, but his activities did not always satisfy the Queen, who on at least one occasion, wished he were dead. Fatigued by political intrigue, in 1597 he retired to Oxford to revive the University Library, and in 1602 the Dean and Chapter of Exeter presented Bodley with almost 100 manuscripts from the Cathedral Library, with the intercession of his brother Lawrence, who was canon at the Cathedral. He died in Oxford in 1613.

Exeter Cathedral Library

The Cathedral Library had grown over the years. In 1050 Bishop Leofric found only five volumes in the minster when he moved the cathedral from Crediton to Exeter, and in about 1070, he donated about 60 volumes to the Cathedral. In 1327 an inventory listed 351 volumes. About 55 were service books and 49 volumes received after the inventory was prepared, chiefly service books, were also listed. The actual total in library was probably a little over 300 volumes.

In 1506 another inventory listed 374 volumes in the library, 327 of them chained in eleven reading desks. A total of 634 volumes in the Cathedral are listed including many service books and some volumes of legal texts, also other works stored in the old treasury and scattered elsewhere round the Cathedral. Some of these had probably been disposed of and replaced by printed texts before 1602 and others disappeared after the gift had been made. By 1752 only 18 medieval volumes remained in the Cathedral Library.

The valuations quoted in the 1327 inventory were converted to 2018 values by comparing today's national living wage with the eleven pence a week earned by labourers working in the quarries for the Cathedral, as recorded in the fabric rolls. This implies that £1 in 1327 was worth the equivalent of £6,000 in 2018, but this should be regarded as an indicative figure only.

The Bodleian gift

There were about 97 volumes in the gift, of which 31 are represented in this talk. Almost half (41 volumes) date from the early 12th century, a period when many volumes were commissioned from Normandy, the 14th century accounts for 20 volumes and perhaps ten date from Leofric's time. Of the 41 volumes of works by the church fathers who lived from the fourth to seventh centuries, Augustine accounts for 17, Gregory for 12, Ambrose for 6, Isidore for 4 and Jerome for 2.

Other early writers from the same period include Bede, Boethius, Johannes Cassanus and Prudentius. Later writers, mainly from the 13th century onwards, account for 22 volumes, including Robert Holcote, Bartholomaeus Anglicus, Robert Kilwardby, Jacobus de Voragine, Thomas Aquinas and Bartholomew, bishop of Exeter (1160-1184). Liturgical and services books are represented by one Bible, one Gospel book, six glosses on the Bible, one penitential, six psalters and one missal. Law, medicine, astrology are among the non-theological subjects represented. We start with manuscripts that were in the library in Bishop Leofric's time.

What follows describes the six manuscripts in the RAMM exhibition (Gatekeepers to Heaven). We will give only the titles for the remainder.

Leofric missal (on display in Gatekeepers to Heaven, RAMM 2023)

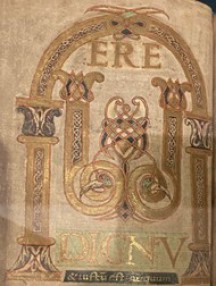

The Leofric missal (MS. Bodley 579) is made up of three manuscripts put together for Leofric.

The image (taken in the exhibition) shows folio 60 verso, the start of the canon of the mass, showing typical insular style decoration with intricate interlacing and generous use of gold leaf.

The missal, or rather sacramentary, forms the main part and was written in Lotharingia, probably in Cambrai or Arras, around 890. Interspersed with this are a later English calendar in Latin, probably from Glastonbury about 970, and various sections written in several different hands, probably when Leofric was bishop in Exeter. These include masses, benedictions, exorcisms and historical matter: fifteen manumissions granted in Exeter and Tavistock dating from 970 and 1050 in Old English, a list of sureties for land at Stoke Canon, a Latin note on bishops and a list of religious relics at Exeter, chiefly given by King Athelstan. The script is a mixture of Carolingian minuscule for the main text with uncials and Roman capitals for the headings. The volume also contains Leofric’s curse against anyone who should remove the volume from the library. The gathering together within a single binding of a variety of often unrelated texts and its use to inscribe legal documents and other records occur in other volumes in the Bodleian gift.

The four gospels (on display in Gatekeepers to heaven, RAMM 2023), open at a page with Leofric’s curse in Latin and Old English

The four gospels (MS. Auct. D. 2. 16) are preceded by the prefaces of Jerome and Eusebius. The manuscript was probably written in Landevennec, Brittany in the 10th century as it includes three feasts of Saint Winwaloe and one for Saint Samson. There are full-page representations of the evangelists before each gospel. The image shows the start of the gospel of Luke, the initial letter Q showing a face, perhaps of the evangelist but not with his normal emblem, the ox, but the depiction of a peacock. Folios 1-2 verso contain a long list of Leofric's donations of lands, church furniture and books and it also contains his curse. There is a list of relics given to the monastery of Exeter, chiefly by Athelstan and neumes, an early form of musical notation.

- Penitential of Egbert.

- Gregory. Penitentiale sancti Gregorii.

Prudentius. Poems (on display in Gatekeepers to Heaven, RAMM 2023)

Prudentius was a Roman Christian poet, born in the Roman province of Tarraconensis, in Northern Spain in 348. He probably died in the Iberian Peninsula around 413. This manuscript of his poems (MS. Auct. F. 3. 6.) was written in England in the mid 11th century. The image illustrates the coloured capitals and copious notes and glosses to the poems. Some glosses are in Old English, and all were probably written before the volume was presented by Leofric to Exeter. The hymn at the bottom of the second column has neumes, an early musical notation. There are also two Old English charms and another version of Leofric's curse, in both Latin and Old English.

In Leofric’s donation list of 1072 it is listed as: liber Prudentii sicomachie. In the 1327 inventory it is valued at 12d. - perhaps £300 in 2018 prices.

Augustine. De civitate Dei (on display in Gatekeepers to Heaven, RAMM 2023)

Augustine's City of God (MS. Bodley 691) is probably the most influential of his works. This early 12th century Norman manuscript has several miniatures in capital letters and illuminated capitals by at least two artists. A few of the 14th century annotations apply sentences in the treatise to events in England. The image shows the Incipit at the base of the second column, preceded by the Retractio (reconsideration) of the author Saint Augustine by way of a preface with an initial I made up of grotesque creatures. At the head of the page is an ownership inscription: Liber ecclesie Exoniensis. In 1327 it was valued at £1 0s 0d – perhaps £6,000 in 2018 prices.

Jerome. On Isaiah (1) (on display in Gatekeepers to heaven, RAMM 2023)

Jerome's treatise on Isaiah (MS. Bodley 717), another Norman product for Exeter, made in around 1100, contains the whole treatise in 18 books with a prologue. It also contains an ownership inscription (14th century): liber ecclesie Exoniensis de communibus.

The image shows the incipit with an elaborate initial V showing Christ enthroned with Isaiah exhorting the people to turn to Him. There is a smaller initial P at the start of the prologue. In 1327 it was valued at one mark (13s 4d £0.67) – perhaps £4,000 in 2018 prices.

Psalms with the glossa magistralis of Petrus Lombardus (on display in Gatekeepers to Heaven, RAMM 2023)

This volume (MS. Auct. D. 2. 8) contains the psalms with the gloss of Peter Lombard and is a late 12th century English manuscript. The image of folio 241 verso shows the whole page, with two illuminated initials. Both initials are part of the marginal gloss by Peter Lombard, which makes up the bulk of the page, the text of the psalm itself being a mere eight lines in a larger minuscule hand.

Peter Lombard (c.1096-1160), born in Novara, was a scholastic theologian, Bishop of Paris, where he died, and author of four books of Sentences, which became a standard textbook of theology, for which he earned the accolade Magister Sententiarum.

The ownership inscription in a 13th century hand threatens anyone who removes the book with eternal malediction.

Medieval manuscript-making

Let us consider then how we may become scribes of the Lord. After looking at these thirty volumes and before we move on to the final section, a consideration of how this medieval library might be recreated, let us look at the spirit in which so many of these manuscripts were copied. A twelfth-century sermon added to a Durham Cathedral manuscript (B iv. 12 folio 37) contains this revealing insight both into the minds of many of the copyists and the methods of manuscript production. It takes each item used in the process of making a manuscript and tells of its spiritual significance.

The parchment on which we write for him is a pure conscience, whereon all our good works are noted by the pen of memory, and make us acceptable to God. The knife wherewith it is scraped is the fear of God, which removes from our conscience by repentance all the roughness and unevenness of sin and vice. The pumice wherewith it is made smooth is the discipline of heavenly desires. The chalk with whose fine particles it is whitened indicates the unbroken meditation of holy thoughts. The ruler [regula] by which the line is drawn that we may write straight is the will of God ...The tool [instrumentum] that is drawn along the ruler to make the line is the devotion to our holy task ...The pen [penna], divided in two that it may be fit for writing, is the love of God and our neighbour ...The ink with which we write is humility itself ...The diverse colours wherewith the book is illuminated, not unworthily represent the grace of heavenly wisdom ...The desk [scriptorium] whereon we write is tranquillity of heart ...The copy [exemplar] by which we write is the life of our Redeemer ...The place where we write is contempt of worldly things.

The diligence of the scribes over the centuries had filled the space available by 1400 and the Cathedral authorities decided to accommodate the manuscripts in the north walk of the cloisters against the south wall of the Cathedral. In 1411 the project to fit out the library was begun. Work was undertaken on Exeter Cathedral Library 1412 and 1413.

Two carpenters were employed. Hamond Jakyl received 2s 6d a week and his assistant Henry Atwater 2s 1d a week (account of works on the Library of Exeter Cathedral 1412-1413, D&C 2669). Detailed accounts for the work survive in Dean and Chapter Ms 2669. The general account of Richard Skinner from 30 Sep 1411-29 Sep 1412 shows his receipts:

- £18 6s 71/2d from the estate of John Lyndewood

- £16 7s 9d from the Steward of Chancery

- £34 14s 41⁄2d Total

The expenses for materials amounted to £7 14s 8d including: 73 shelving boards; 5 boards for desks and seats; 350 board nails; Also -

drink given to the carpenters by the steward's order (8d) (account of works on the Library of Exeter Cathedral 1412-1413, D&C 2669).

The wages of the carpenters for 40 weeks from July 1412 to April 1413 came to £9 3s 6d (account of works on the Library of Exeter Cathedral 1412-1413, D&C 2669).

Expenses incurred in binding books and other matters including some work undertaken at Ashburton came to £18 15s 51⁄2d (account of works on the Library of Exeter Cathedral 1412-1413, D&C

2669).

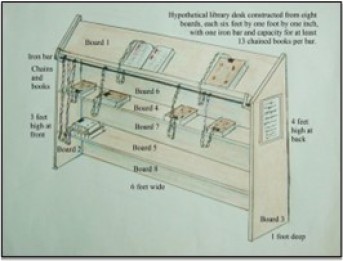

Evidence from the accounts lists:

- For furniture: 73 shelving boards; 5 boards for seats; 350 nails; 12 iron bars This is sufficient for up to 12 desks each made up of six to eight boards fixed with 24-32 nails.

- For books: 253 calfskins, sheepskins and redskins; 121 sheets for guards; 163 books stitched; 194 chains. This is sufficient to rebind and provide with chains up to 194 volumes (16 per desk). There were perhaps 150 volumes already bound and provided with chains.

The pound in your pocket: some leaves from the magic money tree.

Ian Maxted's calculations show that, based on the wages of the two carpenters £1.00 in 1412 is equivalent to £4,000 in 2020. Total income for fitting out the library in 1412 was £34 14s 41/2d. Total expenses for fitting out the library was £35 13s 71/2d. So Richard Skinner almost kept to budget. Equivalent budget for library project in 2020 would be around £142,000 and the over-run less than £2,000. Modern planners of large projects have much to learn from the medieval Cathedral authorities.

The growth of Exeter Cathedral Library 1070-1506

1070: 65 volumes given by Leofric 1327 324 volumes in the library (also 116 elsewhere)

1412: 194 volumes were bound and provided with chains

1506: 374 volumes in the library chained to 11 desks (also 260 elsewhere).

There were few printed items in 1506 – the most notable exception is five volumes of Abbas super decretales (probably Venice: Johannes de Colonia and Johannes Manthen 1475-1480 or possibly

Basel: Johann Besicken, 1480-81 based on 2nd folios).

Duke Humphrey's Library and Hereford Cathedral chained library

The manuscripts of Exeter's gift to Bodley were moved into Duke Humphrey's library, newly provided with desks by Thomas Bodley. Their appearance can be examined more closely in Hereford Cathedral chained library, established in 1611 by Thomas Thornton, Canon of Hereford.

Zutphen chained library, Netherlands

The library from which they were moved in Exeter was very different, lacking the shelves above the reading desk. Two such libraries survive in Europe: Zutphen library was built in 1564 as part of the church of St Walburga. Sixty keys to the front door of the library were issued, not only to the canons, but also to selected townspeople.

Bibliotheca Malatestiana, Cesena, Italy

The Malatestiana Library in Cesena was purpose-built from 1447 to 1452 and opened in 1454, and named after the local aristocrat Malatesta Novello, perhaps the first civic library in Europe, belonging to the commune rather than the church or a noble family, and open to the general public. Unlike Zutphen library this had shelves below the desk to hold additional volumes.

Hypothetical library desk

Based on the provision of six to eight boards, one iron bar, and 24-32 nails per desk mentioned in the accounts and the requirement for shelves below the inclined reading desk to accommodate the number of volumes assigned to each desk in 1506, which range from 14 to 49 in the inventory, this hypothetical design for a Cathedral library desk can be drawn up.

Location of medieval Library

These desks can be fitted neatly in to the 1412 library in the north walk of the cloister, since demolished but now with a project in progress for rebuilding the cloisters.

Richard Parker’s reconstructed drawing

Richard Parker's reconstructed drawing includes a cut away to show the library complete with readers. James Willoughby has recently completed a 190 page account of the Cathedral library, transcribed all surviving medieval booklist and related them to surviving manuscripts in Oxford, Exeter and elsewhere as part of the Corpus of British Medieval Library Catalogues, a British Academy project started in 1990. With all this current interest, and the information outlined in this talk, could the medieval library be reincarnated digitally in its original location?

Libraries in Exeter

Cathedral Library has survived for almost a millennium but it has had its ups and downs both before and after 1602 and this is also true of other libraries in Exeter. In medieval times, monastic libraries reflected the world vision, dominated by the theology of the church of Rome, the writings of the church fathers, liturgcal works, and the Code of Canon Law.

The dissolution of the monasteries led to a decline in learning just at the time when the Renaissance and Reformation were opening people’s minds to the heritage of the ancient world and a wider vision. Few institutional libraries stepped in to take the place of monastic libraries; in the 16th century both the Cathedral Library in Exeter and the University Library in Oxford languished.

There were no publicly accessible libraries in Exeter in the 17th century. The presence of the Cathedral hindered the development of separate parish libraries like those in some other Devon towns within the city, and such libraries as were to be found were the private collections of clergy, lawyers, merchants or gentry with some small collections in schools.

During the 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment, things began to change. Donations were still made to the Cathedral Library, notably the medical library of Dr Thomas Glass in 1786. The Exeter Library Society formed a subscription library in 1776. Book Clubs were formed, including the Exeter Reading Society, recorded in 1792.

Circulating libraries, often attached to bookshops are recorded from the 1780s and survived into the 20th century. The most notable foundation of this period, which still survives today, is the Devon and Exeter Institution, established in 1813, but there was, in the 19th century, a host of other libraries and reading rooms, for example the Exeter Mechanics’ Institute, the Exeter Medical Library, the Exeter Law Library, the Athenaeum and the Exeter Scientific and Literary Institution. It was perhaps the proliferation of such bodies which meant that Exeter was relatively slow in adopting the Public Libraries Act of 1850.

Only in 1869 was it adopted, and Exeter City Library opened as part of the Royal Albert Memorial, that cultural Catherine wheel that spun off the sparks, not only of the public library but also the University Library and the College of Art Library, now part of the University of Plymouth. For a century the City Library built up extensive lending, reference and local studies collections, severely hampered by the blitz of 1942, and in 1974 it was absorbed by Devon County Libraries to become part of Devon Library Services.

Austerity in 2011 led to Devon County Council outsourcing library provision to Libraries Unlimited in 2016, but not before library restructuring in 2012 had removed all specialist posts and moved the Westcountry Studies Library to the Devon Heritage Centre on Sowton Industrial Estate where it is now administered by the South West Heritage Trust from Somerset with services from a librarian from Taunton one day a week. Amid all this change the Cathedral Library flourishes, and it would be satisfying to see the reconstruction of at least one desk in situ with some sort of virtual reconstruction of the entire library as it was in 1506. Perhaps this could be a project encouraged by the UNESCO City of Literature.

[ Ian Maxted / Sue Jackson ]