Semper Fidelis:

The Civic Community of Exeter and the Memory of the Western Rising of 1549

by Professor Mark Stoyle, Wednesday, 6 August 2025

Our Chairman, Neil Ward welcomed us all to the Historic Guildhall, with a special welcome to both our speakers for the afternoon. He then introduced our first speaker - Professor Mark Stoyle.

Neil gave a short biography of Mark, who grew up in Devon, and, after leaving school, worked for a time as a field archaeologist in Exeter. He is currently Professor of early modern history at the University of Southampton and has particular research interests in the English Civil War, in witchcraft and in Tudor rebellions. His latest book, The Western Rising of 1549, has just been published by Yale University Press in paperback. Mark has served on the Council of the Royal Historical Society, on the advisory board of the Victoria County History and on the editorial advisory panel of BBC History Magazine. He has also appeared on more than 60 radio and TV programmes.

Mark's talk was entitled Semper Fidelis: The Civic Community of Exeter and the Memory of the Western Rising of 1549

.

Mark commenced his talk by welcoming us all on this significant date — August 6th which commemorates Jesus Day

. This was

uniquely celebrated in Exeter for 300 years.

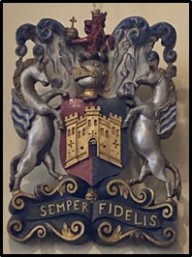

Mark set the scene by explaining that the Guildhall (in which we were sitting) was the centre of Government in the city, in the same way that the Cathedral was the centre of religious life. The Coat of Arms is displayed on the wall at the back of the room and displays the motto of Exeter — Semper Fidelis (ever faithful). This motto is also to be found on Apple Taxis, on some versions of the Exeter football shirt, on the Polish squadrons shield, a nd on the Devon and Dorset regimental cap badge, among others. Since the 1450s, the city had a shield with the castle on a red and black background. It was reputed that Elizabeth I granted Exeter the motto in 1588, in gratitude for monies given which helped to enable the defeat of the Armada. However, this is not documented, so it seems more likely that Exeter's town governors simply concocted the motto.

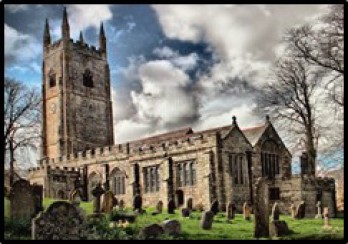

Mark explored the origins of the Western Rising — pointing out that it was the disestablishment of the church, under Henry VIII that unsettled the country, and, on the accession of Edward VI in 1547 with his Protector Edward Seymour, a full-on drive to establish Protestantism was initiated. Religious discontent became widespread, and on Whit Monday 1549, an argument broke out between two members of the congregation of Sampford Courtenay and the parish priest. This was caused by the nature of the new service which had been held by the priest, according to the new statutory Book of Common Prayer. Within a week, the church had become the centre of a major political protest. This escalated, and the councillors in London sent an army to suppress the rebellion. The rebellion was led by locals, supported by the Cornish, and the aim seemed to be to establish Mary Tudor (Catholic) on the throne, or as regent for Edward VI, currently a boy king. Exeter was besieged, as the Town Governors had closed the city gates, thwarting the entry of the rebels into the city.

When Lord Russell and his troops eventually defeated the rebels and lifted the siege on 6th August 1549, the Mayor and City Governors met with Russell outside the City Walls and congratulated him on his victory, while he, in turn, congratulated them on holding out for the Crown for so long. All now seemed set fair for the City authorities, who hoped to be rewarded for their loyalty, as Russell was by now Earl of Bedford, and William Cecil (Protestant and anti-Catholic) was Secretary of State to Edward VI. In December 1550, the Manor of Exe Island was granted to the Civic authorities in Exeter in a new charter. (Henry Courtenay, who had formerly owned the manor) had been executed in 1538, which had also offered opportunities to the new Protestant establishment in the West Country.

Sadly, for the town governors, Edward VI died in 1553, and Catholic Mary I ascended to the throne. The power of the Church in Exeter was now in the ascendant, while the Civic elite was more at risk. William Cecil was removed from office, and Russell, Earl of Beford died.

From 1553-1559, no reference was made in local civic documents to the events of 1549. But Protestant sympathies were growing among the Exeter elite. At this point, John Hooker (born 1527) became Exeter’s City Chamberlain in 1555. Mark praised Hooker as an influential and balanced administrator. His office chiefly concerned the orphans, but he was also to see the records safely kept, to enter the acts of the corporation in the absence of the town clerk, to attend the city audits, to survey the city property, and to help and instruct the receiver. It is owing to him that so many of the city records were preserved intact. In his book, Mark termed him ‘the first and most important chronicler’ of the disturbances, although he warned that his ‘accounts also contain biases and distortions’. Hooker played a vital role in helping to create the image of Exeter as a community united in its loyalty to the Crown.

Mary died in 1558 and was succeeded by the Protestant Elizabeth I — to the relief of the city elite! Soon afterwards, Queen Elizabeth granted a formal charter to Exeter's new Company of Merchant Adventurers, which stipulated that 49 wealthy men should meet on August 6th at the meeting to elect the new Governor of the company. This formed a perpetual commemoration of the defeat of the Western Rising.

Mark went on to show that the ruling elite in Exeter subsequently exploited the memory of the Prayer Book rebellion for all they were

worth and were rewarded for their loyalty to the Crown when the Royal Herald granted Exeter “supporters” (figures standing on either side) to its coat of arms on 6th August 1564. At some point over

the following years, an annual civic commemoration of the relief of the city on 6 August was instituted. Known as Jesus Day

, this commemoration involved a civic procession to the Cathedral, a

special service, a civic banquet, and riotous revelry for local people in the city at large. In 1572, Hooker published a pamphlet showing the new Coat of Arms with the motto “Floreat in aeternum,"

which translates to May it flourish forever.

In 1637, the formal motto became “Fidelis in Aeternum” (Eternally faithful). There had, in fact, been a struggle between two competing religious

factions in Exeter during the mid-16th century. But the curated memory of 1549, which was established during the Elizabethan period, commemorated unity! On the eve of the Civil War, the zealously

protestant town governors were very proud of their reputation for eternal fidelity, but, when the crunch came, they decided that they were more faithful to their protestant God than to their

allegedly pro-Catholic king, Charles I, and chose to turn rebel themselves! During the opening year of the Civil War, in 1642-43, the city was held for the Parliament. After a long siege by the

king's army, it was restored to the royal allegiance in September 1643, only to be recaptured by the Parliamentarians again after yet another siege in 1646. Yet, following the restoration of the

monarchy in 1660, Exeter's town governors were quick to erase all trace of their Parliamentarian past and to proclaim to the world that they were eternally loyal, just as they had done before. In

1665, we find the first record of Exeter's present-day civic motto: “Semper Fidelis”, ever faithful – and that has continued to be the wording of the motto ever since. But, as Mark noted at the end

of his talk, the true history of Exeter’s relationship with the crown during the Tudor and Stuart periods is more complicated than that motto might suggest!

Judith Hosking (kindly edited by Mark Stoyle)