WEATHER & WAR

with Nicola Gale at Jurys Inn, Exeter

on Thursday, 13 August 2020

What a great moment to be back in Jurys for another fascinating talk about former times. Today it was the history of the Met Office and its connection – and usefulness – to war planning. Our lecturer explained that her interest was triggered by hearing someone explain that Exeter was so devastated by the bombing in 1942 because the wind swept up the High Street thereby spreading to horrific effect the havoc caused by those incendiary bombs.

In 1914, the Met Office representations were turned down by the military. Studying weather was considered a trivial, even frivolous, occupation irrelevant to the seriousness of war planning. And of course the war was to be over by Christmas. France and Belgium would be freed, the Germans sent back to their own country and all would be back to normal.

But the war was still ongoing in April 1915 when Germany launched its first gas attack near Ypres. Retaliation was inevitable but our systems were not very sophisticated. They simply comprised

opening a cylinder containing gas and hoping it would have a suitable effect. Our first retaliation at Loos on 25 September 1915 failed because the wind unexpectedly changed direction and it was our

own troops who were gassed, not the enemy.

A scientist from the Met Office, Ernest Gold CB, DSO, FRS, produced a report covering the relevant 24 hours over 24/ 25 September. His report collated information from observers all over Europe. It showed the variations in weather and concluded that the sudden and unexpected change at Loos could not have been predicted.

The enemy were also having problems with weather prediction. They sent Zeppelins to attack London and unexpected weather conditions meant that they missed the capital and hit the coastline all the

way up to Hull instead!

War always brings about great change and so it was in WW1 when our tanks and machine guns were improved significantly and the science of the Met Office was recognised at last.

Ernest Gold was an expert on upper air and higher wind and this information was considered crucial, particularly to aviation, and eventually the British High Command were persuaded that the Met

Office’s information was useful. The number of observers was increased and they fed back information to the Met Office every 4 to 6 hours. From these reports engineers provided the army and the Royal

Flying Corps with wind, rain and temperature information. They even provided gas alerts for enemy gas attacks on us.

Those planning the war effort were too busy to study and analyse statistics. They required direct statements of weather in plain English so as to factor in that infor-mation when planning attacks which in turn enabled them to decide whether to move forward or delay. The Met Office collated all the information provided to them from observers all over Europe, the UK and Ireland and produced the infor-mation the planners needed. Those synoptic charts covering the next 24 hours were produced every four hours and were the forerunners of the reports civilians still receive today, such as “Snow in the mountains” or “Fair tomorrow” etc.

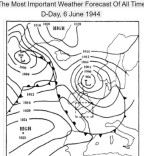

To divert: Dangerous storms were predicted around D-Day. The planners were warned that to invade during those storms would mean

losing more men than in the invasion itself. But the scientists predict-ed a 24-hour gap in the storms on 6 June 1944 and that was the day chosen for D-Day. This meant only a one-day delay on the

plans when it could have been a fortnight. And who knows what the outcome would then have been – certainly the delay could have meant our plans becoming known to the ene-my.

It is now known from studies of rain during 1915-1918 that the rain was exceptionally heavy during that extended period so the planners had no

choice but to work around it.

And topology was not on our side: our trenches were on lower land than the enemy’s so our flooding was worse.

GAS:

Met Office reports were heavily relied on by the Royal Engineers in charge of plan-ning gas attacks. Forecasting the weather meant they were also able to establish the rate of travel of the gases as

many (particularly chlorine) quickly deteriorated with time. On the Western Front the Met Office scientists were also able to help with the selection of gas sites as the lay of the land would affect

the effectiveness of the gases.

Much of this contravened the Hague Convention but everyone was doing it so it felt justified! Our lecturer observed that most military historians, on examining all the detail of war, became

pacifists!

AVIATION:

Aviation was used in the American Civil War but then it mainly consisted of people throwing bricks from balloons.

World War I threw up new demands on the Met Office. Temperature and wind speed were essential information and Gold’s specialism in upper winds was partic-ularly useful. Early aircraft were made

mainly of balsa wood and canvas so were extremely vulnerable.

The Met Office had had pre-war connections with the Royal Flying Corps so they knew exactly what information the pilots wanted. The relationship between the two organisations was greatly

strengthened by the war and as a result the Met Office was subsequently absorbed into the RAF.

ARTILLERY:

Basically the practice had always been to lob shells fast and quickly and hope for the best. But during the Boer and Crimean wars a more scientific approach was being considered. For instance,

objects travel at different speeds in different tem-peratures so the range can be adjusted accordingly.

During WW1 the Met Office scientists provided information which greatly in-creased the effectiveness of shells fired. Working out the right range depended on the mass of information which the Met

Office provided so that the range could be adjusted according to the weather. When firing could be heard in Kent this was because shells were firing so high into the upper air that the sound carried

across the Channel.

WW1 became the first technological war. So much was changed. For instance, at the start most transport was by horses subsequently replaced by machines.

The Met Office became hugely important during the Second World War – as, for instance, in the planning of D-Day – and we know that meteorolo-gy was integral to the decision on when to bomb Hiroshima

and Nagasaki.

We know very little about the Cold War but can be certain that one day many secrets will be released about the contribution made by the Met Office to planning both during the Cold War and in

subsequent years. For example, in the present times the pilots of drone attacks are usually many miles (even thousands) away from the conflict itself, so need detailed weather reports to ensure

success.

The Met Office has become essential and integral to everyone’s daily life. For instance, cadets planning to hike on Dartmoor first phone the Met Office – it may be too cold or too hot, particularly

for kids. Even the army is weather dependent. Having not been taken seriously in the early days, planners and generals now greatly value the Met Office forecasts.

In closing, our speaker pointed out how the huge data set of information on rain and weather now provided is also helping us to see how the climate is changing. For instance, the Met Office

comparisons of weather in September every year since WW1 show important changes and these greatly contribute to our under-standing of climate change.

We all applauded our speaker for an excellent and stimulating talk which left us with so much to think about. Also, all agreed that it was wonderful to be able to get out and learn some new facts in

a different environment. Our socially dis-tanced seating made it very comfortable for the audience and reassured us all that we were as risk free as we could ever be.