On two consecutive Wednesdays we met for a guided walk around some little known landmarks. Our first plaque, just off Southernhay, was dedicated to Violet Barnes who was determined to become an actress and, against her father’s wishes, went to London at the age of 18. Encouraged by Dame Ellen Terry, she was given some stage roles and changed her surname to Vanbrugh. She then toured America and on her return took on many Shakespearean roles.

Her younger sister Irene joined her, appearing in the premiere of “The Importance of Being Earnest”, J M Barrie’s “The Admiral Crighton” and works by Somerset Maughan. In the early 1900s she performed before King George V at Queen Alexandra’s birthday party and in 1941 she was made a Dame.

Moving further along Southernhay we came to the plaque dedicated to Theodore Bayley Hardy VC, DSO, MC, Army Chaplain, who was the most decorated non-combatant of the First World War. With his dogged determination to be with the soldiers at the front, he proved to be a shining example of courage, humanity, bravery and loyalty. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order on 31 July 1917, a Military Cross on 4 October 1917 and finally his Victoria Cross when in April 1918 he was wounded in action whilst crossing a footbridge accompanying a fighting patrol near Cambrai. He died on 18 October 1918. Three weeks later the war was over.

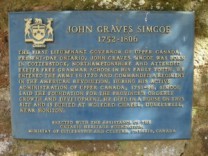

On Cathedral Close we admired two plaques, the first dedicated to John Graves Simcoe, 1752 – 1806. He distinguished himself during the American war of independence, being wounded three times and rising to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, before returning to Exeter to convalesce. in 1791 he returned as Lieutenant Governor of the new province of Upper Canada. One of his achievements was commencing the abolition of slavery there - years before it was abolished in the British Empire as a whole.

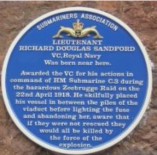

On the same pathway was a plaque honouring Richard Douglas Sandford, 1891-1918, submarine commander & VC who, at 26 years old won the Victoria Cross for taking part in the Zeebrugge Raid which aimed to prevent German submarines from accessing the Bruges Canal. As he approached the harbour in his explosive-filled submarine, German soldiers raked the vessel with small arms fire and laughed for they thought he had accidentally run aground. He skilfully placed the vessel between the piles under the bridge then laid his fuse and abandoned ship. He and his crew escaped in a skiff and rowed to the open sea still under intense fire. By coincidence, he was picked up by his brother who was commanding a motor launch which had been laying a smoke screen. Sadly, Sandford died of typhoid fever at Eston Hospital, North Yorkshire, on 23 November 1918, just twelve days after the signing of the Armistice.

This statue in Cathedral Green represents Richard Hooker, 1554 – 1600, writer and theologian, and dates from 1907. It is sculpted from white Pentilicon marble from Greece and the base is made from granite from Blackingstone Quarry, Moretonhampstead. Richard Hooker is shown holding an open book depicting his most famous work,”Of The Laws of Ecclesiastical Politie.”

Hooker was an Anglican priest and influential theologian and was exceptional in promoting religious tolerance. His words on the arches speak of man and nature living harmoniously together within a framework of divine order. Hooker’s philosophy was intended to cement the Elizabeth Reformation. His uncle, John Hooker was Chamberlain of Exeter and wrote an early history of the city and it was a distant descendant of Hooker’s uncle who paid for the statue.

Franz Liszt, 1811–1886, Composer and virtuoso pianist, gave two recitals in the Clarence on 28 and 29 August 1840. Among Liszt’s compositions for piano that year is a short piece called Exeter Preludio, presumably written while in Exeter. it lasts only 20 seconds. This celebrated pianist, whose flowing locks, slim figure and mesmeric personality made him the equivalent of rock star of the period—ladies were known to swoon at his concerts!

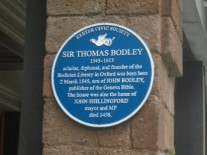

Sir Thomas Bodley, 1545 – 1613. In 1555 Bodley’s father went into exile in Europe with his wife, his children and the boy Nicholas Hilliard who had been placed with the Bodleys by his father (Nicholas Hilliard subsequently became renowned as a portrait miniature painter as well as a goldsmith). In 1580 Thomas Bodley returned to England to the court of Queen Elizabeth but he is best remembered today for the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The library had suffered greatly during the Reformation and Bodley set about restoring it. He spent a considerable amount of his own money on the library and brought in books from many places, approximately 80 volumes – including medieval manuscript books. A sizeable part of his fortune was left as an endowment to the library and he was buried in the choir of Merton College, Oxford.

On Queen Street, Queen Victoria’s statue and cupola on the roof of B&S were removed when the original building, condemned as unsafe, was demolished in 1980. The statue of the young Queen Victoria was too damaged to reinstall but was replaced in fibreglass moulded from the original. The typically Georgian whole side wall facing Queen Street was rebuilt from precast concrete sections moulded from the original design.

This handsome building was originally the old infirmary providing medical treatment to the poor. Dr Hennes, of cholera fame, was one of the practitioners. It was established in 1818 for what was called “the gratuitous supply of medicine and professional advice to the indigent poor”.

The building was erected on a plot of land previously occupied by the Victoria Hall. Built to accommodate 2,000 people, it caught fire in the night and five Fire Brigade Office vehicles couldn’t save the building.

A curious happening during the fire was the sound of scales from the organ – not the result of a foolish musician but just the heat forcing air through the organ’s pipes !! The heat was so intense that the Rougemont Hotel nearby suffered

HARRY HEMS was a prolific architectural and ecclesiastical sculptor, born in London, but long-time resident in Exeter. His first employment in Exeter was as a sculptor for the Albert Memorial Museum, then being constructed. This workshop was erected in the 1880s. At the peak of his activities he employed over 100 men and provided sculptures and fittings to over 700 churches, some 100 public and other secular buildings. In Devon the roodscreens of Kenn, Littleham and Staverton churches are notable examples of his work, but perhaps his best known achievement was the restoration, at a cost of £12,000, of the great altar screen of St Alban’s Cathedral in Hertfordshire.

He clashed with the law more than once over assaults on employees and he was fined twice for non-payment of taxes but he was generous in his help to local hospitals and his charitable work. His creative legacy in wood and stone is still to be seen in Exeter, for example the Livery Dole Martyrs Memorial.

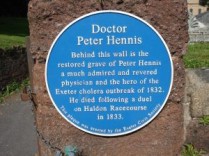

Finally, Irish-born Dr Peter Hennis (1802 – 1833), hero of the 1832 Exeter cholera outbreak, came to Exeter in 1830 and secured the position of physician to the Exeter Dispensary. This provided care for the poor and “children considered unfit to be admitted to The Devon and Exeter Hospital”. Dr Hennis devoted much of his time to their care. During the cholera outbreak in 1832, he was appointed medical officer to the poorest of the city where his reputation for kindness and hard work grew.

In May 1833, Sir John Jeffcott, an Admiralty Court judge, falsely accused Dr Hennis of maligning him and a duel with pistols was organised. It was agreed the opponents would face each other 14 paces apart and two words of command would be used: ‘Prepare’ and ‘Fire’. On 10 May at 4.30 p.m., Sir John fired prematurely, fatally wounding Dr Hennis who did not return fire.

Having received forgiveness from Dr Hennis, Sir John left the country for Sierra Leone the next morning. Peter Hennis, who was due to wed the following month, died eight days later suffering a slow, lingering, painful death.

He was the last man killed in a duel in Devon and the city was outraged. 250 dignitaries attended his funeral service at the Cathedral and 20,000 citizens lined the route to St Sidwell’s Church where he was interred, such was the depth of feeling toward him. It was one of the largest gatherings ever seen in the city. However, attitudes towards duelling were changing at last and the last recorded duel in England was in 1845.

St Sidwell’s continues to help the poor and needy and now runs a vegetable garden to teach young dispossessed people and also offers training in restaurant skills. Where else to stop for a cup of tea and home made cake !

Finally, our thanks to Diana Taylor of the Civic Society for all her dedicated research leading to a very interesting presentation accompanied by a most enjoyable guided walk around Exeter.

Should you wish to visit more plaques, we cannot recommend highly enough that you consult the Civic Society website:

https://www.exetercivicsociety.org.uk/?post_type=plaques

This will provide you with full details of all the plaques and their locations in Exeter. Happy hunting !

To return to the home page click on "Home Page" on the banner at the top of this page.

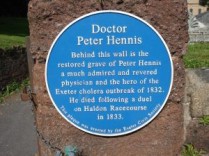

Finally, Irish-born Dr Peter Hennis (1802 – 1833), hero of the 1832 Exeter cholera outbreak, came to Exeter in 1830 and secured the position of physician to the Exeter Dispensary. This provided care for the poor and “children considered unfit to be admitted to The Devon and Exeter Hospital”. Dr Hennis devoted much of his time to their care. During the cholera outbreak in 1832, he was appointed medical officer to the poorest of the city where his reputation for kindness and hard work grew.

In May 1833, Sir John Jeffcott, an Admiralty Court judge, falsely accused Dr Hennis of maligning him and a duel with pistols was organised. It was agreed the opponents would face each other 14 paces apart and two words of command would be used: ‘Prepare’ and ‘Fire’. On 10 May at 4.30 p.m., Sir John fired prematurely, fatally wounding Dr Hennis who did not return fire.

Having received forgiveness from Dr Hennis, Sir John left the country for Sierra Leone the next morning. Peter Hennis, who was due to wed the following month, died eight days later suffering a slow, lingering, painful death.

He was the last man killed in a duel in Devon and the city was outraged. 250 dignitaries attended his funeral service at the Cathedral and 20,000 citizens lined the route to St Sidwell’s Church where he was interred, such was the depth of feeling toward him. It was one of the largest gatherings ever seen in the city. However, attitudes towards duelling were changing at last and the last recorded duel in England was in 1845.

St Sidwell’s continues to help the poor and needy and now runs a vegetable garden to teach young dispossessed people and also offers training in restaurant skills. Where else to stop for a cup of tea and home made cake !

Finally, our thanks to Diana Taylor of the Civic Society for all her dedicated research leading to a very interesting presentation accompanied by a most enjoyable guided walk around Exeter.

Should you wish to visit more plaques, we cannot recommend highly enough that you consult the Civic Society website:

https://www.exetercivicsociety.org.uk/?post_type=plaques

This will provide you with full details of all the plaques and their locations in Exeter. Happy hunting !

To return to the home page click on "Home Page" on the banner at the top of this page.

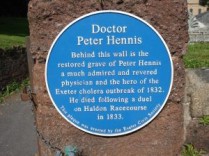

Finally, Irish-born Dr Peter Hennis (1802 – 1833), hero of the 1832 Exeter cholera outbreak, came to Exeter in 1830 and secured the position of physician to the Exeter Dispensary. This provided care for the poor and “children considered unfit to be admitted to The Devon and Exeter Hospital”. Dr Hennis devoted much of his time to their care. During the cholera outbreak in 1832, he was appointed medical officer to the poorest of the city where his reputation for kindness and hard work grew.

In May 1833, Sir John Jeffcott, an Admiralty Court judge, falsely accused Dr Hennis of maligning him and a duel with pistols was organised. It was agreed the opponents would face each other 14 paces apart and two words of command would be used: ‘Prepare’ and ‘Fire’. On 10 May at 4.30 p.m., Sir John fired prematurely, fatally wounding Dr Hennis who did not return fire.

Having received forgiveness from Dr Hennis, Sir John left the country for Sierra Leone the next morning. Peter Hennis, who was due to wed the following month, died eight days later suffering a slow, lingering, painful death.

He was the last man killed in a duel in Devon and the city was outraged. 250 dignitaries attended his funeral service at the Cathedral and 20,000 citizens lined the route to St Sidwell’s Church where he was interred, such was the depth of feeling toward him. It was one of the largest gatherings ever seen in the city. However, attitudes towards duelling were changing at last and the last recorded duel in England was in 1845.

St Sidwell’s continues to help the poor and needy and now runs a vegetable garden to teach young dispossessed people and also offers training in restaurant skills. Where else to stop for a cup of tea and home made cake !

Finally, our thanks to Diana Taylor of the Civic Society for all her dedicated research leading to a very interesting presentation accompanied by a most enjoyable guided walk around Exeter.

Should you wish to visit more plaques, we cannot recommend highly enough that you consult the Civic Society website:

https://www.exetercivicsociety.org.uk/?post_type=plaques

This will provide you with full details of all the plaques and their locations in Exeter. Happy hunting !

To return to the home page click on "Home Page" on the banner at the top of this page.