The Gatekeepers to Heaven

A members' visit to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum for a guided tour of the special exhibition of the medieval manuscripts

by Assistant Curator Tom Cadbury on Thursday, 17 August 2023 at 2.30pm

A group of Society members assembled to meet Tom Cadbury at the Garden entrance of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM). We were keen to see the Gatekeepers to Heaven

exhibition, with the bonus of exploring the exhibition with its knowledgeable curator.

Tom began by giving us some background information - apparently this exhibition was 3-4 years in the making and involved quite

complicated arrangements, as all the manuscripts need a careful climate-controlled environment - even when in transit! Ian Maxted (who gave our society a talk entitled Grievous Bodley Harm

in June this year) was involved in the mounting of the exhibition, and his talk gave a most

interesting background to the visit to the RAMM to see the six manuscripts in all their glory. The Exhibition is entitled Gatekeepers to Heaven

as it refers to the two

powerful Bishops that were most influential in the history of these manuscripts.

Bishop Leofric is the first. He founded the Cathedral in 1050 (though not in the current Cathedral building). He found a dearth of material in his new diocese and endowed the Cathedral with the founding collection of manuscripts. The second of the Gatekeepers is Bishop John Grandisson, who restored control and established order in the Cathedral after the murder of his predecessor Bishop Walter de Stapledon in 1326. Grandisson was a reforming Bishop who expanded the Library, updated the liturgy, and instituted moral reforms among his lax clergy. These two towering personalities became the “Gatekeepers to Heaven” in this exhibition.

The Gatekeepers and Thomas Bodley

Thomas Bodley (pictured left) was born in Exeter in 1545. When he returned from exile in France, he became a diplomat. On his retirement to Oxford in 1597 he decided to establish a Library. The medieval manuscripts, featured in this exhibition, all belonged to Exeter Cathedral (along with about 90 others) and were part of a gift made by the Dean and Chapter in 1602 to Bodley’s new Bodleian Library in Oxford. The gift was probably facilitated by Thomas’s brother Laurence, who was a Canon in the Cathedral at the time.

The six books (in seven volumes) in the Exhibition were described in detail by Ian Maxted in his fascinating talk to ELHS in June.

The manuscripts were originally used daily for services, but then got older and were superseded by newer volumes. The manuscripts (made of vellum, and bound in calfskin), were eventually left to moulder on shelves, and were affected by what is known as Exeter mould - particular to this area. There is little doubt that they have been much better preserved in the Bodleian Library!

The first volume is the Leofric Missal, made in Canterbury and Exeter between 850-1070, (now rebound in two volumes) and presented to Exeter Cathedral by Bishop Leofric himself. The Missal contains masses, blessings, calendars, and the tables for working out the dates of feasts, such as Easter. There is also musical notation, possibly added by Leofric.

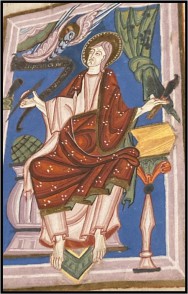

The Leofric Gospels

The Leofric Gospels were made at Landévennec Abbey, Brittany, with later additions from St. Bertin and Exeter, between 920 and 1070. It is written in Latin and depicts the Gospel writers with their animal symbols in place of their heads. An unusual depiction. Around a century later, further French additions were made to the manuscripts, including the addition (see left) of the lovely depiction of St. John. During Leofric’s time in Exeter the manuscript was used to record relics and also deeds of land belonging to the Cathedral, written in Old English.

Prudentius—Various works with added charms in Old English

In addition to the previous manuscripts, the exhibition displays a collection of works by Aurelius Prudentius Clemens (348-413) in Old English. He was a Roman Christian poet, philosopher, and politician. The manuscript in the Exhibition shows the interrelation between religion, magic, and medicine in the medieval world. The page displayed shows an Old English Charm and is a charm to protect against nosebleeds. Tom explained that charms were less magic (as we understand it) and more of a treatment or remedy. Homemade medicine was the only cure available for ailments. The charm mentions quern stones and an alder tree. Maybe the advice involves grinding the bark of the alder tree to staunch the bleeding. It is hard to decipher, which is why Tom was unsure as to its precise meaning. It is written in a mixture of Old English and Old Irish. The charm may have been added to the documents, as there was a spare piece of vellum in the manuscript, which would need to be used up. Vellum was very expensive!

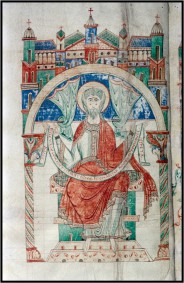

Jerome ‘s Commentary on Isaiah

Jerome ‘s Commentary on Isaiah is the next manuscript to be viewed in the Exhibition. It is a copy of St. Jerome’s Latin commentary (made at Jumiége Abbey around 1060-90. This may have been part of the Leofric collection or may have been a later addition. It shows the Prophet Isaiah seated in a temple with a great city (probably Jerusalem) behind him (see left). The facing page shows the scroll with Jerome and Eustachious (a saint and abbess) to whom the work was dedicated. Towards the end of the manuscript is the wonderful self-portrait of the scribe and artist Hugo Pictor (Hugo the Painter). Probably the earliest signed self-portrait ever. This manuscript was certainly in Exeter Cathedral Library in 1327 as it is in the Library Catalogue, valued at 13 shillings and 4 pence. Bishop Grandisson labelled it as part of the Cathedral library. In 1506 it was the 9th book on the 9th desk.

The first of the final two manuscripts was produced in Normandy, with later additions in Exeter. The first is Augustine-De Civitas Dei. This is a copy of the “City of God” written by the North African philosopher Augustine of Hippo in around 430 AD. The decoration was probably added in England 200 years later, probably by at least 2 scribes, probably commissioned by John Grandisson to bring the manuscript up to the required standard. The final manuscript is the Psalter with the gloss of Peter Lombard, 1150-1200. It contained the Old Testament book of Psalms along with other prayers, and is lavishly illustrated with decorative animals, birds, mythical creatures, and foliage.

When Tom had given us all a chance to look closely at the manuscripts and to read all the information, he took us around the other exhibits in the exhibition. Among other objects there are examples of pottery, which demonstrate that in medieval times there was a French potter working in Exeter within the City Walls. One of the finest exhibits is the Puzzle Jug (part of the RAMM’s permanent collection). It was made in France in the 14th century and found in South Street.

With thanks to Tom Cadbury for a fascinating tour of this amazing exhibition.