Martha’s Memories

The Later History of St. Nicholas Priory

with Ben Clapp on Thursday, 11 January 2024

at 7pm at The Mint Methodist Church

Our speaker Ben Clapp works at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter and is a trustee of Exeter Historic Buildings Trust. St Nicholas Priory, Exeter’s oldest building, has had a long history, including its time as a monastery and many years as a grand Tudor home. Ben’s sixteen years’ involvement with the Priory through his job at the RAMM and now as a volunteer has enabled him to research more of its later history. Ben’s talk was accompanied by a wealth of photographs and images and this write-up will be a brief overview of what was a very interesting evening.

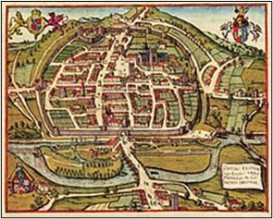

The monastery was founded in 1087 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The foundation was Benedictine, with the monks sent from Battle Abbey. It remained a cell or branch of Battle Abbey until its dissolution. Ben showed an image of the Priory’s seals from the 1916 guidebook. He also showed a map and the appropriate section of the Hedgeland model and the Hogenberg map of Exeter in the RAMM to indicate its location.

The buildings had an unusual arrangement, the Church was on the South side rather than the North side – this may have been to provide more living space, or maybe to give more prominence to the Church towards the main street.

There were usually no more than twelve monks and a Prior at a time, and the Church had the right to ring bells, a privilege normally only allowed to the Cathedral. This caused some friction between the two establishments. By the time of the Dissolution the monastery owned land all across the South West – (including Cullompton Parish church) and it had an annual income of £147-12s a year.

The Priory was dissolved in October 1536. The religious parts of the Priory were got rid of first, and some of its fixtures and fittings moved elsewhere in Exeter. The Church, Chapter House and Dormitories, and the South and East ranges were all demolished. Some of the stone was used to repair the City Walls and the Medieval Exe Bridge. John Hooker (Elizabethan historian) reported that there were riots, and a group of local women broke into the priory while the demolition was taking place, and the foreman had to escape by jumping out of the church tower. However, the protests were unavailing, and the demolition continued.

Turning old churches into town houses was quite common, and the Priory was no exception.

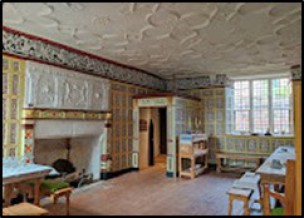

The building went through several owners after the Dissolution, probably due to property speculation, before becoming a Tudor home in 1562, owned by the Mallett family (as in Shepton Mallett). The Malletts didn’t live there, but leased it out to middle class tenants, including the Hurst family. These were local wool merchants, and one of them was the grandson of a Mayor of Exeter. William Hurst put in the parlour plaster ceiling in the 1570s. The family lived there for about 50 years until about 1602.

After the Civil War, buildings like the Priory began to look quite old fashioned compared with brick built buildings like the Notaries House on Cathedral Green, built in the late 1600s. The Mallett family were Royalist, and now began to suffer some financial problems, and consequently sold off some of their properties, including parts of the Priory estate. At this time Mint Lane was cut through part of the Priory, and the whole building began to look a little run down. There used to be an archway through Mint Lane, though now that is all gone. In 1700 the archway was cut through and it was then demolished in 1864.

The last wealthy person to live in the building was Nathaniel Cosserat. He was a grandson of a Huguenot refugee from France. Nathaniel was a city Alderman, and he was Mayor in 1786. He was prominent in the wool trade and died in1796. He only owned the West range of the Priory, but he didn’t seem to have any heirs. When he died all his goods were auctioned off, and the record of the auction is still in the archive. The extent of the Priory buildings can be seen in the Hogenberg map (see above), and in the Hedgeland model, which is in the Ramm. Much of the grounds had been sold off by this time.

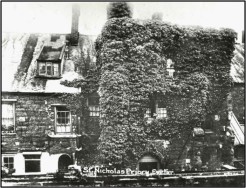

The Regency and Victorian eras saw a decline in the Priory building. In about 1820 the Wilcoxes bought the West Range and sub divided it into tenements. The West range by now was in a bad state and was described as a mere rookery of tenements. It can be seen in this picture, covered in ivy and dilapidated in 1900. Demolition was considered.

At this time the Undercroft was used as a kitchen. The building was in a state of general disrepair. The sisters of St. Wilfred’s used it to supply penny breakfasts for the poor. The sisters used the Great Hall as a creche and looked after the babies while their mothers worked. The babies were picked up at about 4.30 – they would have had a bath and a clean napkin.

Ben had obtained evidence of what it was like to live in the Priory from various sources, one being the memories of Florence Emma Tapscott. He supplemented these memories by images of the various rooms within the building. Upstairs, in the bedroom above the parlour, Florence Tapscott (later Gilpin) had been born in the Priory in 1892. She lived there with parents and her brother. In the 1970s she recorded some of her memories. She loved the window seat where she would sit to read and do her homework. They had to move out when it was turned into a museum. Florence moved to Bartholomew Street later on.

The Parlour/Tudor room’s plaster ceiling has survived remarkably well. The Priory had original panelling that had been removed by the Wilcox family and taken to Monkerton Manor in Pinhoe. It was never recovered. The current panelling that you can see in the West Range today is originally from a Tudor house in Exeter High Street (one beyond the current Urban Outfitters that was lost in the Blitz). This panelling was sold in 1953 to a museum in San Francisco. It was recovered in 1999 by John Allan and installed in the Priory in 2001.

The Kitchen was separated from the main building in 1820 and became part of a three-storey house, and evidence of the removal of a window can be seen in the brickwork from the lane. A Mrs Scott lived there as No. 13 Mint Lane with her husband and four children. Evidence in the 1921 Census showed that the family had subsequently moved further down Mint Lane. Ben showed an image from an 1888 insurance map and a photo of the wooden screen in the Great Hall. The Catholic Church bought the Refectory and used it as a meeting place before it became a school (21 The Mint) and then a caretaker’s house. Apparently, at one stage it was used as a gym, and locals also learnt to roller skate and cycle in there and had parties.

When the building was divided, the kitchen became a 3-storey house (13 The Mint). Elsa Ann Scott was pictured outside the house in 1913 – one of the last tenants in this part. Her husband was a candle maker, they had 4 children and her elderly father living there.

The 1900s saw a move to save the building and in 1909 Mr Harbottle-Reed, architect, drummed up interest. The City Council were petitioned to save the building and purchased it in 1913. Four people were responsible for saving the building – Sir Harold Brakspear (1870-1934), and H. Lloyd Parry (1865-1950) Town Clerk, Lewis Tonar (1860-1940) and Octavius Ralling (1858-1929). These last two were also responsible for saving several buildings in Exeter and elsewhere in the country. Harold Brakspear was skilled in restoration, and wrote the 1916 guidebook to the priory. He was present at the opening of the building and led a tour of the building. Lewis Tonar liaised with the press but it is unclear how hands-on he was in the actual restoration. He was a member of Exeter City Council. His business partner was Octavius Ralling who was born in Colchester, was employed as a trainee architect before going into partnership with Lewis Tonar. The firm were responsible for saving several buildings in Exeter and around the country. Ralling drew the Priory 17 years before he worked on it. He wanted to recreate the grandeur of the building and to rejoin the two wings of the building. His drawings were painted rather than drawn. He was very involved with the actual work. He painted a coat of arms for John Grenville, an Exeter MP from 1550-1555, and this was found in the Priory on 14th April 1914.

Sadly there is only one photograph of the progress of the restoration of the Priory. Restoration finished and the West Wing was opened to the public on the 1st November 1916. Lewis Tonar was present at the Grand Opening. The Mayor was presented with a silver key, and given a guided tour of the building by Harold Brakspear. Octavius Ralling did not seem to be present. The opening hours were on Tuesdays and Thursdays 10.00-1.00 and 2.00-4.00 (6d entry) and entry free on Saturdays 2.00-4.00 though that was scrapped as there was some vandalism of the Norman pillars in the Undercroft, resulting in the suspension of the free Saturday opening.

The Curators: (the dates reflect their time in the post).

The first curator was Maud Tothill (1916-38) She was eccentric, but well respected. Miss Tothill was born in 1872 in Exeter. After moving to Dorchester, she returned to Exeter, and was appointed as curator earning £65 per year. Miss Tothill kept numerous pets. In her time there, the Priory was very popular, with lots of international visitors, which was surprising in the midst of WW1. She had a guinea pig and a rabbit upstairs. Downstairs she kept Martha the raven, and also Martha’s companion George. It was reputed to be George who used to take the trilby hat round to visitors to raise money for his mutton bones. Martha the raven is the Priory’s longest resident, and she has been there for 90 years! When Martha died there was an obituary in the Devon and Exeter Gazette for her. She was then stuffed and displayed. The remaining raven (George) was lonely after Martha’s death until someone donated another raven (called Honk) to keep him company. When Miss Tothill retired, she gave George to Exeter College for his retirement. Miss Tothill died in 1959 and was cremated in Torquay. Honk’s fate is unknown.

The second curator was Miss H. M. Upright (1938-1957). She is recorded as visiting Monkerton Manor in 1950 to see the panelling which had been removed from the Priory in 1881. She saw the panelling and described it as being in a good state of preservation, although it had been stored in the attic. However, Monkerton Manor was in a dilapidated state and was subsequently demolished (1960s). It is unknown what became of the panelling.

The third curator was Lorna Needham (only in post from 1957-1959). She also tried to retrieve the panelling, with no success. She was born in Devon but lived most of her life in Canada.

The final curator was Jacqueline Warren (1959-1973). She was French but had settled in Exeter. While at the Priory she wrote articles and kept trying to promote the Priory. To her great indignation she was made redundant in 1973 when the Museum took over the Priory. She protested for several years.

Subsequently there were plans to change the Priory into Exeter’s local history museum and to create a peace garden. In the 1970s Exeter ceased to be a unitary authority, and funding changed, so this never happened. In the period between 1996-2002 the North wing was saved and restored by Exeter Historic Buildings Trust. Between 2005-2007 the West Wing closed for refurbishment including the installation of the rescued Tudor panelling into the parlour. In 2014 the West Wing closed again due to structural problems. In 2018 the repairs were completed, and the West Wing was handed over to the Exeter Historic Buildings Trust in a ceremony with the Lord Mayor. Martha the Raven continues to watch over the Priory from her glass case. What would her thoughts be now?

With thanks to Ben Clapp for his help in producing this write up, and to Sue Jackson for her impressive note taking.

[ Judith Hosking ]